Mezzotint History and Technique

|

"The copper-plate it [the mezzotint] is done upon, when the artist first takes it into hand, is wrought all over with an edg'd tool, so as to make the print one even black, like night: and his whole work after this, is merely introducing the lights into it; which he does by scraping off the rough grain according to his design, artfully smoothing it most where light is most required …"

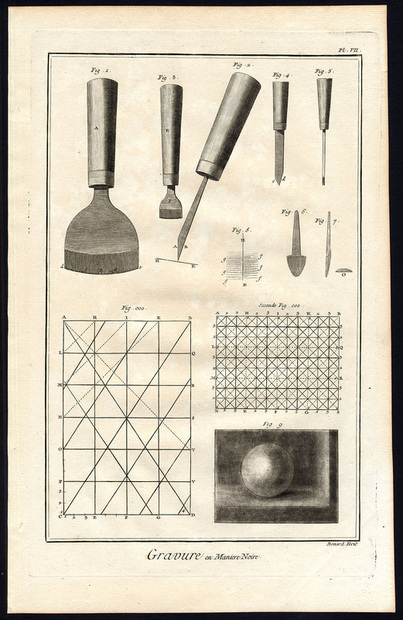

–William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty (1753) Mezzotint (from the Italian mezzo-tinto, meaning “half-tone”) is an intaglio printmaking process, technically a drypoint technique. The plate, most commonly copper, is grounded by making a number of overlapping passes across the surface using a curved blade or "rocker" which is rocked from side to side as it is moved forward. The toothed blade is pushed into the copper, pitting the surface and throwing up small burrs which hold ink. The quality of the ground achieved is dependent on the pressure applied, the speed, number and density of the passes, the angle at which the blade is honed and held and the number and closeness of the teeth (usually 25-100 teeth per inch). The number of passes made by the rocker across the plate will vary according to to the needs of each artist. Generally, 20- 70 passes will be enough, though some may choose to make further passes. Hand rocking is physically demanding and time consuming and a number of mechanical means of ground production have been developed using either a mechanised rocker or a toothed drum rolled over the plate. However, rolled plates in particular tend to lack the tonal range of those produced by rocking and machined plates in general produce a very regular pattern which is not always acceptable. A modern mezzotint rocker |

Illustration showing rocker and rocking patterns.

A fully rocked plate when inked will print a rich black. Mezzotint is a maniére noire ("black method", in which the image is worked from dark to light) technique requiring the reduction of the burrs using scrapers, burnishers or other abrasive tools to reduce the height of the burrs (and consequently the amount of ink which will be held in the plate surface) either by slicing or by pushing the burrs down. You can see a plate in progress in the photograph above. The level to which the burrs are reduced determines the amount of ink held and thus the tone of the area which has been worked in this way. The image is gradually produced by this method. Areas may be darkened using a roulette and additional linear work may be achieved with a drypoint needle. In addition to the nature of the platework, the appearance of the printed image is affected by the texture and dampness of the paper and the quality of the ink used.

|

History.

The mezzotint process was first developed in Amsterdam in the late 17th century. Two amateur foreign artists- German lieutenant-colonel Ludwig von Siegen and the exiled Bohemian, Prince Rupert of the Rhine- arrived at the technique virtually simultaneously, but independently. Prince Rupert’s one-time assistant, Wallerant Vaillant, a French born painter, became the first professional engraver in mezzotint and the technique grew in popularity over the following decades, particularly in London. There, in the middle and later years of the 18th century, the technique dubbed la maniére anglais would experience a golden age. By comparison to etching, few artists used mezzotint as a means of original expression. Instead, from the time of its invention, the mezzotint served primarily to publicize oil paintings. In the second half of the 18th century leading portrait and subject painters worked with mezzotint engravers to produce reproductions of their works, which were frequently exhibited alongside their painted prototypes. During this period mezzotints were widely circulated and collected. By the mid 1770s the mezzotint lost favour to the technique of stiple engraving, which had the benefits of withstanding longer print-runs than mezzotint (the surface of a mezzotint plate is worn with each run and fades considerable after relatively few prints have been pulled) and having the possibility of printing colour a la poupée. Apart from a brief revival in the mid 19th century, due to the introduction of steel faced plates which permitted larger editions, mezzotint fell largely into disuse as a reproductive technology. Throughout its history, mezzotint was used to a lesser extent to produce original prints and although the technique is employed relatively rarely, a number of 20th century and contemporary artists, particularly in Japan, have continued its usage.

The mezzotint process was first developed in Amsterdam in the late 17th century. Two amateur foreign artists- German lieutenant-colonel Ludwig von Siegen and the exiled Bohemian, Prince Rupert of the Rhine- arrived at the technique virtually simultaneously, but independently. Prince Rupert’s one-time assistant, Wallerant Vaillant, a French born painter, became the first professional engraver in mezzotint and the technique grew in popularity over the following decades, particularly in London. There, in the middle and later years of the 18th century, the technique dubbed la maniére anglais would experience a golden age. By comparison to etching, few artists used mezzotint as a means of original expression. Instead, from the time of its invention, the mezzotint served primarily to publicize oil paintings. In the second half of the 18th century leading portrait and subject painters worked with mezzotint engravers to produce reproductions of their works, which were frequently exhibited alongside their painted prototypes. During this period mezzotints were widely circulated and collected. By the mid 1770s the mezzotint lost favour to the technique of stiple engraving, which had the benefits of withstanding longer print-runs than mezzotint (the surface of a mezzotint plate is worn with each run and fades considerable after relatively few prints have been pulled) and having the possibility of printing colour a la poupée. Apart from a brief revival in the mid 19th century, due to the introduction of steel faced plates which permitted larger editions, mezzotint fell largely into disuse as a reproductive technology. Throughout its history, mezzotint was used to a lesser extent to produce original prints and although the technique is employed relatively rarely, a number of 20th century and contemporary artists, particularly in Japan, have continued its usage.

Workshops.

If you are interested in learning more about this technique, follow me on facebook for updates on upcoming workshops.

If you are interested in learning more about this technique, follow me on facebook for updates on upcoming workshops.